Greece – Culture, Politics and War

The evolution of the political system in ancient Greece was closely mimicked by the evolution of war itself. When most people think of ancient Greece they think of their philosophy, theater, democracy, the hoplite soldier and so on. What most don’t realize, however, is this view of ancient Greece only applies to a certain period: the Classical Age of Greece. The Classical Age is when Greek influence truly began to spread along with Greek culture. Greek warfare became focused around the hoplite and phalanx formation. Athens dominated the sea with their navy and Sparta dominated the land with their unstoppable army.

Ancient Greece

The Political System of Sparta

Ancient Greece - Spartan Agoge

Most, if not all, of the reasons for Spartan dominance on the battlefield can be attributed to their incredibly strenuous and brutal training regiment, the agoge. Even before beginning the agoge, newborn Spartan boys underwent a highly in-depth physical scrutiny to make sure the newborn was without flaws. Any that did not pass the examination were left out in the country to die. Then, between ages five to seven, the boy was taken to begin training. There were no fond farewells, boys were simply taken to live in barracks as a “pack” or unit and encouraged from the start with competitive play against other packs.

Most, if not all, of the reasons for Spartan dominance on the battlefield can be attributed to their incredibly strenuous and brutal training regiment, the agoge. Even before beginning the agoge, newborn Spartan boys underwent a highly in-depth physical scrutiny to make sure the newborn was without flaws. Any that did not pass the examination were left out in the country to die. Then, between ages five to seven, the boy was taken to begin training. There were no fond farewells, boys were simply taken to live in barracks as a “pack” or unit and encouraged from the start with competitive play against other packs.

By age 10 they had been taught to read and write and their physical exercise was increased. An important activity was dancing (of all things) with their weapons until all movement with the weapons became ingrained and natural. Movement was the key to the warrior’s success and the ability to freely move was paramount. By 12 they would have learned all of the Spartan war songs and their military training would begin in earnest. The journey to manhood also meant they would have their hair cut short, their tunics would be taken away and instead they were given a cloak in its place to fend off whatever the elements threw at them.

To toughen their feet they would go barefoot at all times and to further the bestial mentality they would eat very little always keeping them aggressive and hungry for more. They were allowed to supplement this diet of course by testing their cunning by stealing, but with a heavy punishment if caught- not for stealing, but for being caught! Severely beaten for any reason the instructors could come up with, training was harsh and brutal. Many boys wound up dying during the course of their training due to its brutality. Those that survived, however, became true Spartan soldiers and were unstoppable in battle.

mentality they would eat very little always keeping them aggressive and hungry for more. They were allowed to supplement this diet of course by testing their cunning by stealing, but with a heavy punishment if caught- not for stealing, but for being caught! Severely beaten for any reason the instructors could come up with, training was harsh and brutal. Many boys wound up dying during the course of their training due to its brutality. Those that survived, however, became true Spartan soldiers and were unstoppable in battle.

Finished with the agoge at age 20, a young man still had to be selected by a group of older peers before he became a homoioi, a full Spartan citizen. From then on, his life would be devoted to the army. Either away at war or at home training and competing against his fellow soldiers for recognition, a Spartan man was always devoted to combat and bettering his ability to make war. Whereas other cities in Greece were noted for their advanced culture such as theater and philosophy, Sparta was famous for the personal fortitude, character, restraint, and moral fiber of people it produced.

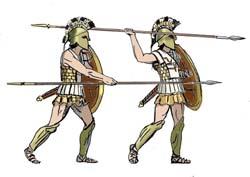

Ancient Greece - The Hoplite

Their main weapon, not the sword as many books and movies would have you believe, was the spear (600074). Rarely thrown, the spear, between 7 and 9 feet long, was held onto providing great reach to the enemy. The lines of the phalanx would stand shoulder to shoulder; shields leading the way. The first rank would thrust from beneath the shield while the rank(s) behind would stab over it. This two pronged attack was rarely countered successfully, because if you covered up your lower body you were skewered from above and if you covered the head you were skewered from below. Any way you look at it, you did not want to be a foe facing this relentless advance.

As a secondary weapon, hoplites often carried a sword into battle. Most commonly used was the two foot leaf shaped blade of iron or bronze (500734). Also used were the falcata (500062) and the kopis (501207). The Spartans had a specially designed blade that was similar to the common leaf shaped hoplite sword except the Spartan sword was barely over a foot long (401178). It was said that the blade could be lengthened by taking a step closer to your enemy!

Finally, most hoplites possessed a cloak of some sort to protect themselves from the elements while out campaigning. Due to their full time, professional army the Spartans provided each of their warriors with a red cloak (881001) that they wore into battle. Tradition tells us that the Spartans wore a red cloak so their enemy would never see them bleed. Showing weakness was not tolerated in way, shape or form.

Phalanx Formations

The Classical Phalanx

Drums beat in the distance, keeping the rhythm of the advance. The hot Greek sun beats down on you under your heavy armor and equipment. The overlapping shields of you and your fellow soldiers keeps you locked into formation, steadily advancing towards your enemy. Several yards out from the enemy line, the order is given to charge. You crash into your opponent’s shield with a sickening crunch; the pushing match has begun. Friendly soldiers behind you push you harder into the enemies’ shields as their allies do the same for them. Placing your left soldier and thigh against the rim of your shield, you push with all your might as you stab through the cracks in the shield wall with your spear. The rank behind you stabs over it. Welcome to phalanx warfare.

Battles would continue like this for over an hour with many men being crushed to death, suffocating in the heat, or being speared by the enemy. Eventually, the line on one side would break and the men would scatter, knowing the battle was lost. These pushing matches were how many experts believe Greek warfare was fought during the late Archaic Age and all during the Classical age, with little variation. But first, what exactly is the phalanx?The phalanx can best be described as a long line of heavily armored men moving in rhythm with each other. As hoplites carried massive shields (881004), these would overlap with the shields of the men next to each hoplite. You defended the man to your left with your shield and the man to your right defended you. This created a solid wall of bronze with iron tipped spears poking out. Drums or other kinds of musical instruments kept the rhythm for the advance. If anyone ran ahead or fell behind, the solid line would be incomplete and severely weakened as a result. Since the phalanx required much concentration and cohesion to maintain, it was only effective at a walk or slow charge and even then, only on flat even ground. Uneven terrain would break up the shape in a heartbeat. In addition to this, attacked from the sides or rear, the phalanx was slaughtered and as this formation was so slow, being attacked in the flanks was a very real threat.

Despite these flaws, in head-on engagements almost nothing could penetrate the solid wall of the phalanx except for another, larger phalanx. The typical phalanx was eight men deep, that is, eight rows of men, and any number of men wide. There are instances of both less and greater ranks of men in various battles though. The hoplite’s main weapon was a spear (600074) between seven to nine feet long. With spears this long, the first two ranks of men would be able to reach the enemy with their spears. Deeper rows would serve as both reinforcements if front row men fell and as pushing weight used to keep pressure on and break the enemy’s line. As a greater physical force than the opponent was required to win, sometimes there would be veteran soldiers in the very rear of the phalanx with swords drawn to “prod” their men on and keep them from faltering.

The Macedonian Phalanx

In addition to reinventing the phalanx, Philip II of Macedon added a very heavy and very deadly cavalry element to his army to compensate for the phalanx’s lack of flexibility, speed, and mobility. He added javelin throwers and heavy infantry in addition to a large variety of other soldiers, all in an effort to make his army more flexible and adaptable. With this army he easily defeated Greek phalanx armies and was able to gain political power over Greece. Upon his death, his son, Alexander, took over Macedon and with the powerful phalanx and army developed by Philip, Alexander went on to conquer the Persian empire. The phalanx, with its mobile yet heavy cavalry wing, helped create the empire of Alexander the Great.

The End of the Phalanx

Ultimately, the phalanx’s lack of flexibility, slow speed and enormous vulnerability on the flanks led to its demise. Roman armies, using highly adaptable formations and advanced battle tactics, were able to defeat the phalanx in all its variations. They exploited its weaknesses, avoided its strengths and wound up conquering all of Greece, an achievement never before done. After centuries of total domination on the battlefield, the phalanx became obsolete. It should be noted, however, that various alterations of the phalanx were used in wars and armies millennia later, albeit limitedly.

Tactics of the Roman Legionarre

he ranks could be several men deep, allowing a fresh man to be rotated to the front when needed so as not to break the formation. This tight wall of men was protected by the large scutum (shield) and it was common for battle to be engaged by raining pilums (spears, 600008) down on their foes. This throwing spear purposefully had a very small head on a long iron shaft that would embed itself in its target and then bend, dragging down with it the impaled target, which was often the opponents shield. This thin iron shaft bending held another benefit - your opponent couldn’t throw it back at you!

Weapons of the Romans

As for their sidearm, the Roman soldier was never far from his trusty short sword, the gladius (500360). The gladius was normally worn on a baldric (200368) and slung over the shoulder to hang across the body on the opposite hip. History shows us most were worn on the right hip for a “pull” draw as opposed to a “cross” draw as this type of draw was impeded by the scutum. There were several patterns of gladius and it was not unusual for mixed types to be in use within the same legion. The hilts were much alike and the blade profiles varied somewhat. The one thing that was always the same is the fact that the broad blade was approximately 20” long and had a very keen stabbing point. This point figured greatly into the fighting style preferred by the troops for it consisted almost entirely of an under hand stabbing motion that was most effective while in tight ranks.

The pugio (401392), or large dagger, was also carried by the legions from the time from the late Republic onward. An interesting note is that a large variety of fighting spear heads has been unearthed and were no doubt used, but where they fit into the actual legion is not well known.

Roman Armor & Clothing

All troopers wore a helmet of steel and brass (300074) plus body armor, either a lorica segmentata (300176), made of steel lames or a lorica hamata, made of steel mail with shoulder doublings.

All troopers wore a helmet of steel and brass (300074) plus body armor, either a lorica segmentata (300176), made of steel lames or a lorica hamata, made of steel mail with shoulder doublings.As for the undergarments, very few articles were worn. There are examples of a loincloth or loose short being worn underneath and of course a long tunic (100042) overtop. During festivals and stately occasions a Roman would not be without his robes or toga which replicated the beautiful free flowing designs of the Greeks. Finally leather sandals (200254) were the common accessory to complete any Roman’s outfit.

Life as a Roman Soldier

Diet in the Roman Army

Whenever possible this monotonous army diet was supplemented with whatever was locally available like pork, fish, chicken, cheese, fruit and vegetables. But the basic ration of frumentum was never far from the soldier’s stomach and formed the basis of their diet. So much so, that when supply difficulties occurred in the grain supply causing other foodstuffs (even meat) to be handed out, there would be discontent among the ranks.

The officers enjoyed a more versatile diet (naturally). Archaeologists working along Hadrian's Wall in northern Britain discovered records of a commander from around AD 100; the records listed pork, chicken, venison, anchovies, oysters, eggs, radishes, apples, lentils, beans, lard and butter. Anyone else getting hungry? Not bad eating for a field officer!

Roman Army Pay

Retirement from Roman Army Service

So this is the army that conquered the “world”- a large force of disciplined men in tight ranks acting as one. Almost nothing of the day could withstand this unrelenting fighting machine.

Ancient Persia & Lydia

Croesus' Wealth Lost By A Helmet

In 547 BC, Cyrus, the Great King of Persia was at war with Croesus, the fabulously rich king of Lydia. Cyrus’s cavalry forces had beaten the Lydians in the field, but Croesus retreated and rallied his troops in a strong defense of Sardis within its stout walls, but at the same time had bottled himself and most of his army up in the capital.

Cyrus sat down to besiege it, but its walls were very high and strong, and the Persian army consisted mostly of cavalry. The cause seemed pretty hopeless, and Cyrus was about to raise the siege when a silly accident gave him the town.

standard of Cyrus the Great

One hot and hazy afternoon a sentry on the walls of Sardis took off his shinning bronze helmet and laid it on the parapet of the wall. He stood there, chatting to a comrade with his back to the parapet, when, lifting his arm to wipe the sweat from his brow, his elbow caught the helmet and knocked it off the wall, and down the rocky slope below. One of Cyrus’s men, idly watching the wall, saw the flash of the falling helmet – and soon saw a Lydian soldier lazily climb over the wall, down the slope below, pick up his helmet and leisurely climb up again. There was obviously a path.

gold coin of Croesus

The Persian soldier went to his captain, who then went to the King. That night a picked force of volunteers, guided by the observant soldier, climbed the path, got over the wall, down into the streets and opened one of the gates to let in the strong force which had been positioned outside. And Sardis fell. Croesus was captured, and all his vast wealth as well, and Cyrus the Great then added Lydia to his Empire of Persia. Not through strategy, but bumbling good luck.